Why do our muscles get weaker with age – and can we do something about it?

[[{“value”:”

Why do our muscles get weaker with age – and can we do something about it?

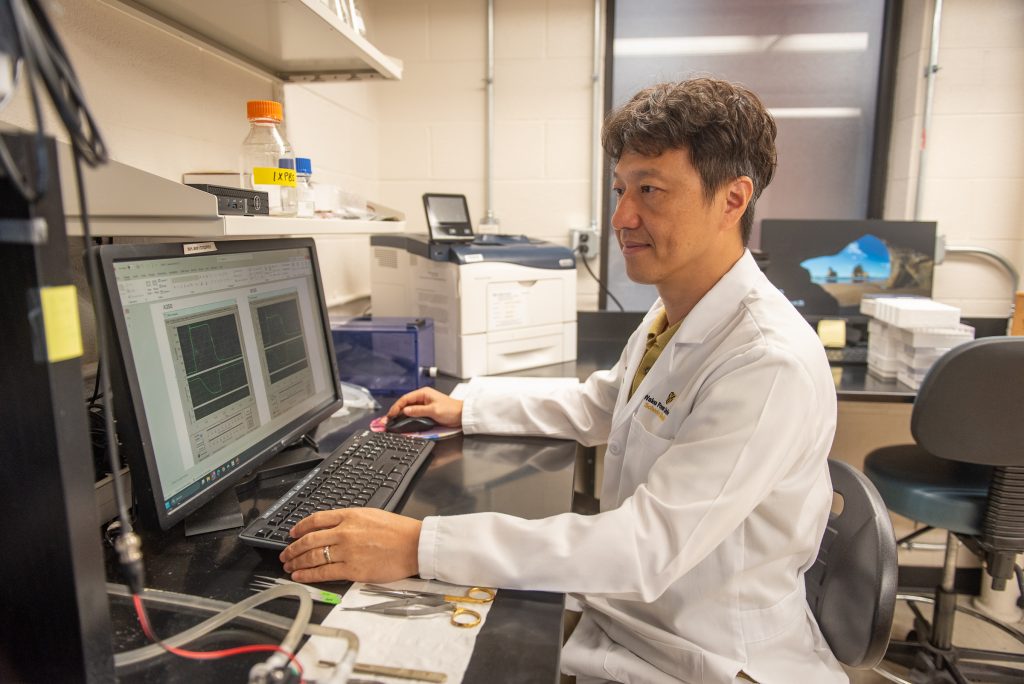

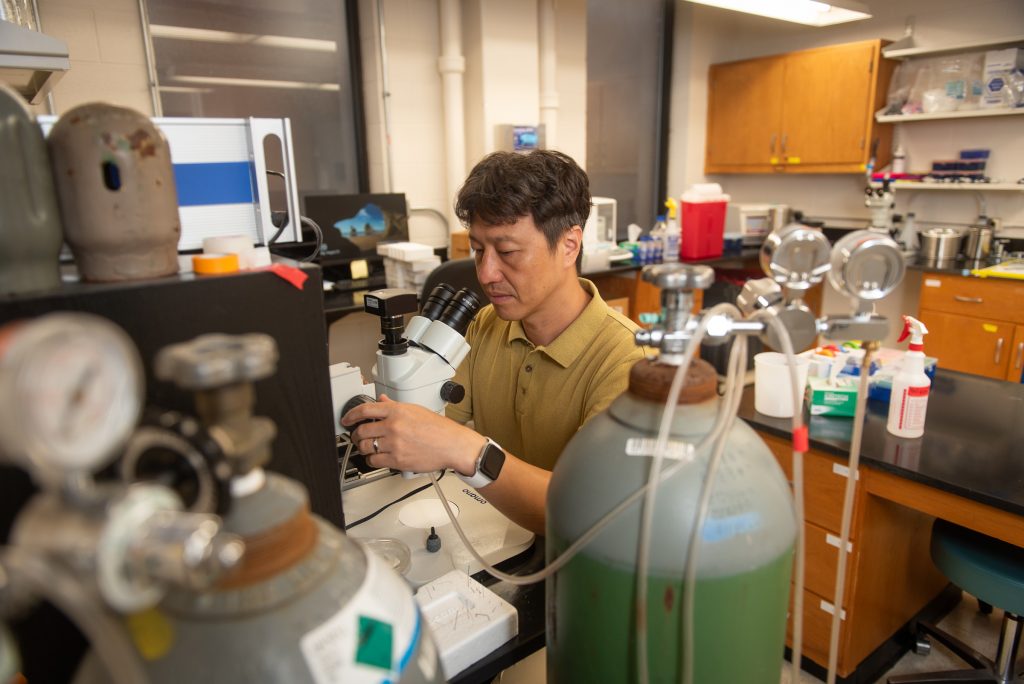

As we get older, our muscles get weaker – a phenomenon known as sarcopenia. The causes of this muscular degeneration are not well understood, although research suggests that functional decline in our mitochondria may be a key factor. At Wake Forest University School of Medicine in the US, Dr. Bumsoo Ahn is studying exercise training and a hormone that has the potential to counteract sarcopenia by improving mitochondrial function. The goal of his lab is to slow the ageing process, allowing people to stay healthy for longer.

Talk like a mitochondrial biologist

Bioenergetics — the field in biochemistry and cell biology that studies how energy flows through living systems

Genome — the complete set of genes in a cell, organelle or organism

Ghrelin — a hormone produced in the stomach, with a range of functions including appetite stimulation

Homeostasis — the biological processes that maintain a stable and constant internal environment within a cell or organism

Mitochondria — organelles found in most cells, responsible for cellular respiration (among other roles)

Oxidative modification — the chemical alteration of biomolecules like proteins, lipids and nucleic acids by reactive oxygen species

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) — unstable molecules that remove electrons from other molecules, causing damage

Sarcopenia — the loss of muscle tissue as a part of the ageing process

In recent decades, human lifespans in developed countries have improved dramatically. However, ‘healthspans’ – the time over which we are healthy and active – have not increased in the same way. Many aspects of age-related decline remain unaddressed, including the loss of muscle mass and function known as sarcopenia. “Muscle mass and function are critical for mobility, independence and therefore quality of life in older people,” says Dr Bumsoo Ahn from Wake Forest University School of Medicine. “Although several compounds for addressing sarcopenia are being evaluated in clinical trials, none have yet translated into effective, widely-used therapies.”

To date, the only effective method for reducing sarcopenia is exercise; however, even the positive effects of exercise decrease as we reach old age. To address this issue, Bumsoo is investigating the biomolecular pathways that lead to sarcopenia – and whether there are opportunities to disrupt them. “The research in my lab aims to find ways to delay sarcopenia so that people can maintain a high-quality lifestyle for longer,” he says.

Bumsoo’s journey

Bumsoo grew up in South Korea (which has one of the world’s highest life expectancies), where he spent much of his time playing sports. “Naturally, this made me curious about the human body, and I wondered why my heart would beat faster during exercise, or how training improved my performance,” he says. “That curiosity sparked an early, though vague, dream of studying human physiology.”

After graduating from university, Bumsoo spent three years working in industry. “Eventually, I realised how much I missed science and decided to return to academia, which ultimately set me on my current path,” he says. “My postdoctoral mentor, Dr Holly Van Remmen, had a profound influence on my career in mitochondrial biology. Working in her lab, I experienced the excitement of scientific discoveries and gained the confidence and curiosity that continue to drive my research today. That curiosity has now turned into a deep desire to uncover how mitochondria support muscle health, and what happens when they fail.”

Mitochondria: may cause side effects

Mitochondria provide our cells with energy via the process of respiration – but this activity is just the tip of the iceberg. “Mitochondria also play central roles in bioenergetics, redox regulation and calcium regulation,” says Bumsoo. “They may have other roles too – experiments using isolated mitochondria only began in the 1950s, and we have a lot left to learn.”

While mitochondria are essential, their hard work does have some unfortunate side effects. “As a by-product of respiration, mitochondria generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) which can cause oxidative modification in proteins, lipids and nucleic acids,” says Bumsoo. ROS take electrons from other molecules, changing the structure and function of these molecules in the process. “The modified molecule then becomes an oxidant itself, which means the effect propagates,” explains Bumsoo. “One ROS can lead to the disruption of countless other molecules.” While ROS are important for cell signalling, these oxidative modifications are generally bad news, as the modified molecules become useless or even harmful. These disruptions can also damage our DNA, accelerating the ageing process.

Muscles are full of mitochondria which allow them to contract, which is an energetically demanding activity. But this high concentration of mitochondria also means a high concentration of ROS and, therefore, oxidative modifications. “The cellular machinery that enables muscles to contract can be inhibited by ROS,” explains Bumsoo. “For example, an enzyme called myosin ATPase, which is essential to muscle contraction, becomes less active when modified by ROS.” Actin – the protein that makes up muscle filaments – is also damaged and becomes less flexible.

The superhero hormone

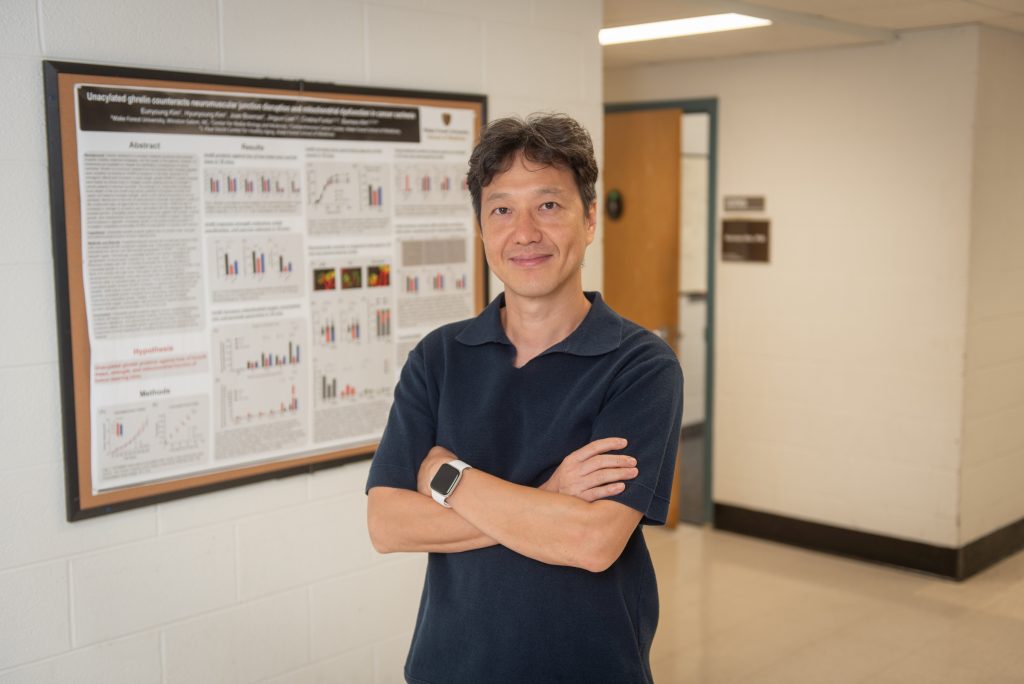

However, Bumsoo is studying a molecular miracle-worker that may be able to rein in all this damage. “Ghrelin is a hormone produced in the stomach,” says Bumsoo. “It is sometimes called the ‘hunger hormone’, but its functions go beyond just controlling our appetite.” For example, a form of ghrelin called unacylated ghrelin appears to be linked to counteracting the loss of muscle mass and function.

Bumsoo conducted experiments showing that unacylated ghrelin counteracted muscle degradation in old mice. It appeared to promote mitochondrial respiration – the process that generates ROS as a by-product – but also mitigated the production of ROS at the same time, leading to an overall positive effect. Ghrelin also appeared to have a protective effect in mice with cancer, slowing the rate of rapid muscle wasting.

From mice to humans

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM653

This educational material has been produced by Wake Forest University School of Medicine in partnership with Futurum and with grant support from The Duke Endowment. The Duke Endowment is a private foundation that strengthens communities in North Carolina and South Carolina by nurturing children, promoting health, educating minds and enriching spirits.

Let us know what you think of this educational and career resource. Simply scan the QR code to provide input.

Ghrelin has been used in clinical trials, but so far only for its role in hunger control. “Prader-Willi Syndrome is a genetic disease that causes constant hunger, as well as other effects including weak muscles,” says Bumsoo. “Patients with the disease who received daily injections of an unacylated ghrelin analogue had positive food-related behaviours without side effects.” Though Prader-Willi Syndrome is very different from sarcopenia, the trial demonstrated that administering the hormone can produce positive results – so perhaps the same could be true for slowing age-related decline. “Our group is keenly interested in developing an unacylated ghrelin analogue that can be swallowed (rather than injected) for a longer-term study with a bigger sample size in the near future,” says Bumsoo.

While ghrelin may prove to be an excellent tool for slowing the ageing process, it will need to work in tandem with other therapies. “My lab is investigating combining pharmacological strategies with exercise regimes to discover the most effective interventions,” says Bumsoo. “Our ultimate aim is to enhance the mobility and independence in older adults for as long as possible.”

Dr Bumsoo Ahn

Dr Bumsoo Ahn

Assistant Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Sections of Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, North Carolina, USA

Field of research: Mitochondrial biology

Research project: Investigating the role of mitochondria in age-related muscle degeneration and how the hormone ghrelin may be able to slow this decline

Funder: US National Institute on Aging (grant number: R00 AG064743); American Federation of Aging Research

About mitochondrial biology

Mitochondria are fascinating organelles: they have a huge range of functions, host complex molecular interactions and continue to present new questions. “Because mitochondria are central to nearly every aspect of human physiology, the field offers opportunities to make meaningful advances in medicine, ageing research and personalised health,” says Bumsoo. “For young scientists, mitochondrial biology provides a vibrant and interdisciplinary career path that connects molecular mechanisms to real-world impact.”

“Mitochondria have multiple roles that are all important for normal functioning and homeostasis,” continues Bumsoo. “They are found in almost all of our cells, with the exception of red blood cells.” Because mitochondria have many and varied roles, many researchers around the world are studying them, each with a unique research angle. “This leads to numerous collaborations, which I find rewarding,” says Bumsoo. “My team and I get to learn about mitochondria in other organs and organisms – it could be in brain slices, blood cells, or fruit flies.”

These research efforts continue to yield new and surprising results, indicating a long and fruitful era of discovery ahead. Bumsoo also predicts that technological advancements will affect the future of the field. “Artificial intelligence, for instance, can accelerate the discovery of mitochondria-targeting drugs, as well as the analysis of imaging to assess incidences of disease,” he says. “A new chapter for mitochondrial biology is just around the corner – it’s a very exciting time.”

Pathway from school to mitochondrial biology

Bumsoo recommends getting a strong foundation in biology, chemistry and physics during school. “These subjects provide the basic principles of energy, molecules and life processes,” he says.

At college and university, Bumsoo suggests seeking courses or modules in biochemistry, cell biology, physiology and genetics. “Beyond undergraduate studies, further training in molecular biology, bioinformatics and data analysis is becoming increasingly important,” he says. “Modern mitochondrial research relies heavily on genomic and proteomic tools.”

If a more applied route appeals to you, biomedical engineering, pharmacology and exercise physiology provide opportunities to develop interventions to improve mitochondrial health.

“You can learn a great deal from hands-on experience, so I would highly recommend seeking opportunities for laboratory experience,” says Bumsoo.

Explore careers in mitochondrial biology

broad camps: academia, which involves primary research, and biotechnology and pharmaceuticals, which involve translating academic discoveries into ways to improve mitochondrial function.

Bumsoo recommends keeping up to date with the latest research. “There is an excellent website that I often use to search for publications related to mitochondrial biology,” he says.

Wake Forest University School of Medicine offers several summer programmes for high school students, including their LEAP Internship Program, which provides STEM lab experience and mentorship, and the Summer Immersion Program, which provides a diverse range of experiences to help students discover their passions and goals.

Meet Bumsoo

During my mandatory army service in South Korea, I had to do parachute jumping as part of a Special Force team training. It was an involuntary and extremely scary experience at the time, but it has now become an interesting memory. Sometimes we don’t see the benefits of our actions until later on.

My career is a bit different than most researchers’ – I worked in the private sector prior to my academic career, and those three years were crucial for convincing me to pursue academia. You don’t need to have your whole career planned out; sometimes, the only way to really know what you enjoy is through experience.

I like that science, at its best, is transparent and based on merit. In research, the data you generate becomes your own scientific credit, regardless of position or seniority. Graduate students and postdoctoral fellows are recognised as first authors for their research contributions. This system of open recognition creates a sense of fairness and accountability that I deeply appreciate.

I also enjoy the collaborative and global nature of science – travelling to conferences, sharing findings and learning from others around the world are privileges that make this career especially fulfilling.

I still exercise a lot, especially running, which helps clear my mind and makes me feel accomplished. I also like to play tennis with my son and chess with my daughter. And when we can, we all go to the mountains to hike as a family.

Bumsoo’s top tip

Dive into whatever excites you right now. The experiences you gain by doing so will help you find the next step of your career.

Do you have a question for Bumsoo?

Write it in the comments box below and they will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)

Learn more about how mitochondrial biology is being used to treat disease:

futurumcareers.com/cancer-biology-with-dr-kelsey-fisher-wellman

The post Why do our muscles get weaker with age – and can we do something about it? appeared first on Futurum.

“}]]