How can we transform carbon dioxide from a greenhouse gas into a valuable resource?

[[{“value”:”

How can we transform carbon dioxide from a greenhouse gas into a valuable resource?

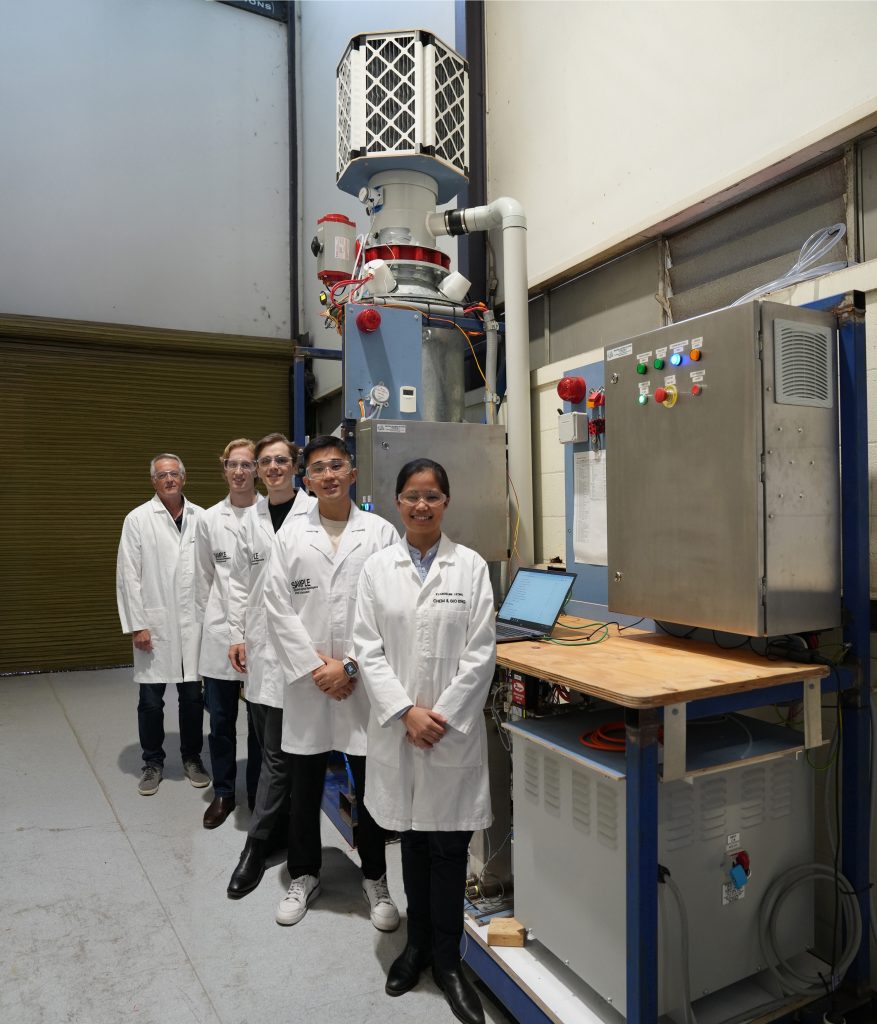

Most climate change mitigation strategies focus on reducing our emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2). However, direct air capture tackles the problem from a different angle: by removing carbon dioxide directly from the atmosphere. At the RECARB HUB, hosted by Monash University in Australia, Evangeline Leong, Maksis Darzins and Dr Aaron Guo have created a new direct air capture system that can supply various industries with CO2, including the biomanufacturing industry which can use this CO2 to create valuable bioproducts.

Talk like a direct air capture developer

Adsorbent — a material that attracts and holds molecules to its surface (not to be confused with absorption, which involves molecules being taken into a material)

Bioreactor — a piece of industrial equipment within which a biological process or reaction takes place

Circular carbon economy — an economic model that aims to keep carbon in circulation, rather than treating it as a waste product

Direct air capture (DAC) — technology that pulls carbon dioxide from the air

Climate change is already having measurable impacts on the environment, ecosystems and human networks around the world. “Carbon dioxide (CO2) in our atmosphere acts as a blanket around the Earth, creating the greenhouse effect that heats our planet,” explains Maksis Darzins from the ARC Research Hub for Carbon Utilisation and Recycling (RECARB Hub) at Monash University. “Human activities have contributed to rising CO2 levels, influencing climate patterns and environmental conditions.”

Mitigating, and ideally reversing, climate change is crucial, and direct air capture (DAC) is likely to be an essential tool in this process as it filters CO2 from the atmosphere. “As well as directly removing surplus CO2 from the atmosphere, DAC can also drive a sustainable future by putting this captured CO2 to good use,” says Maksis. “DAC has the potential to replace fossil fuels and create a circular carbon economy with a neutral carbon footprint.”

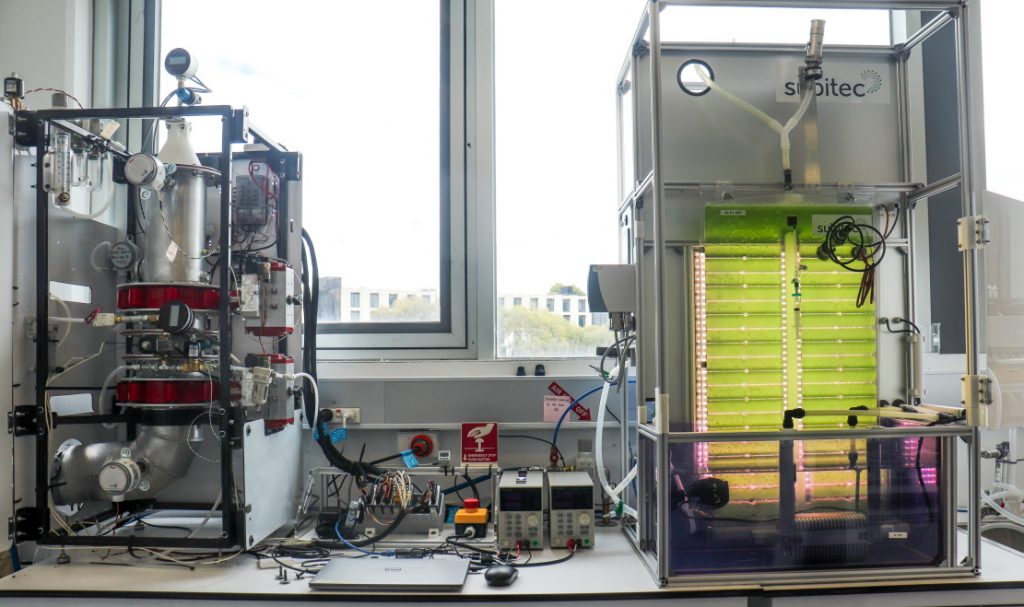

Direct air capture

Sucking CO2 from the air is nothing new. Plants and other photosynthetic lifeforms have been doing it for billions of years. However, it is unlikely that these organisms alone can absorb enough CO2 to fully address climate change. This is where new technologies come in. “The technology that we are researching uses a solid adsorbent to capture CO2 molecules,” explains Maksis. “Once the adsorbent is saturated with CO2, similar to a sponge becoming saturated with water, we heat the adsorbent so it releases the CO2, which we collect using a vacuum system.” The adsorbents can then be reused to capture more CO2.

Interestingly, the team’s system does not rely on one specific adsorbent material. “We are tackling the mechanics of our design first, while remaining open about the materials we use,” says Maksis. “This flips the standard DAC design process, allowing us to tackle the issues facing other DAC systems – in particular, energy efficiency and cost – without being too preoccupied with adsorbent design and synthesis.” This means that the system can use whichever adsorbent is most effective in any particular context, without needing to redesign the entire system. “This modular package gives us the ability to scale up and work with new contractors and industries, increasing the productivity of our system,” says Maksis.

Miraculous microbes

The next stage of the process is figuring out what to do with the captured CO2. “The CO2 produced through DAC technology has a negative carbon footprint (it reduces the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere), so it has potential to be a valuable resource,” says Maksis. “CO2 is already used in various applications, such as carbonating drinks or increasing plant growth in greenhouses.” This CO2 is conventionally produced through fossil fuel combustion, so DAC offers a much greener approach.

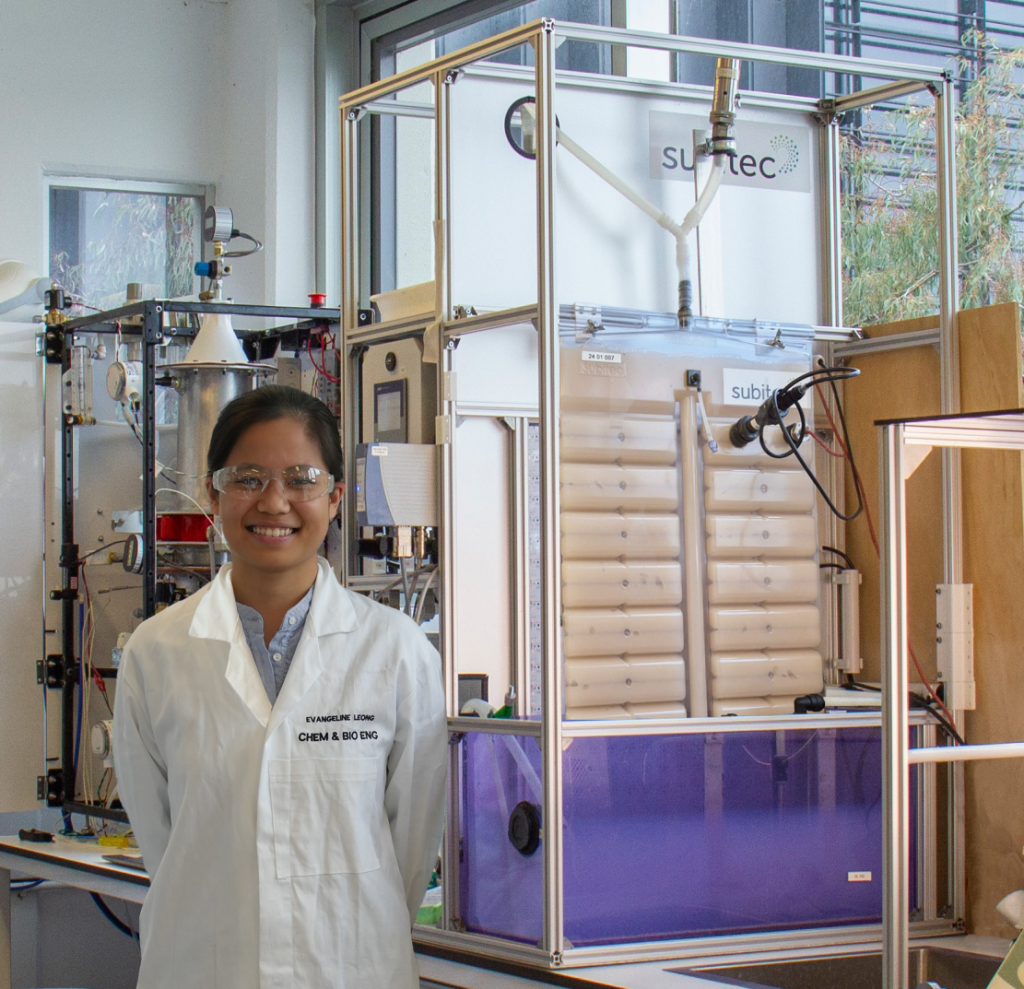

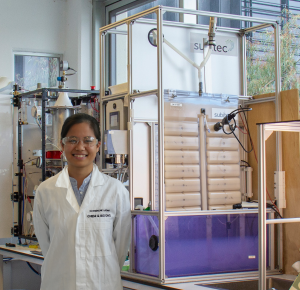

Some DAC systems inject and store the CO2 in rocks underground; however, the team’s DAC2BIO programme takes a different approach. “We are developing systems that feed captured CO2 into bioreactors to grow microbes,” says Evangeline Leong, the primary investigator of DAC2BIO. “These microbes utilise the CO2, alongside hydrogen and other gases, to make specific chemicals, proteins or biomaterials.” This process (known as bioconversion) is often used in biomanufacturing industries to convert waste materials into valuable products. “By integrating DAC with biomanufacturing pathways, we are showing how innovative methods can help industries be both climate-positive and resource-efficient,” says Evangeline.

Given that carbon forms the backbone of all organic molecules, the range of potential products derived from CO2 is large and diverse. “CO2 is increasingly used to produce synthetic fuels and chemicals that would otherwise be made from fossil fuels,” says Evangeline. “And through biotechnology, we can use microbes to convert carbon dioxide into proteins, bioplastics or other sustainable materials.”

Industry partnerships: from research to reality

The team is working with a number of industry partners, bringing together different facilities, resources and expertise. “For instance, Woodside Energy provides engineering expertise and facilities for large-scale integration, helping us understand how DAC can work within real industrial environments,” says Evangeline. “Local manufacturing companies, such as KDR Compressors and Rudimental, contribute to the development of the post-capture gas purification and compression systems while global industry partners, such as WesCEF, BASF, and Agilent, support the team in other ways.”

Such partnerships also bring challenges. Research and industry tend to work on different timescales, there are differences in the way technical terms are used, and systems have to be established for sharing intellectual property. “But the benefits far outweigh the challenges,” says Evangeline. “Together, we’re building not just a technology, but a whole ecosystem capable of transforming atmospheric CO2 into real-world products.”

To date, the team has piloted a small-scale DAC system, which captures CO2 at concentrations suitable for use in a bioreactor. They have also developed a bioprocess that can make biomaterials such as biodegradable plastics. “The next step is to integrate the DAC system with the bioreactor,” says Dr Aaron Guo, another member of the team. “Our aim is to demonstrate a small integrated DAC2BIO prototype that shows the complete production line from carbon capture through to bioconversion.” The long-term aspiration is to scale up the technology so it can make a tangible difference – both in terms of tackling climate change and supporting carbon-positive industries. “We hope our work will contribute to a circular carbon economy, where atmospheric carbon becomes a renewable resource rather than a waste product,” says Aaron.

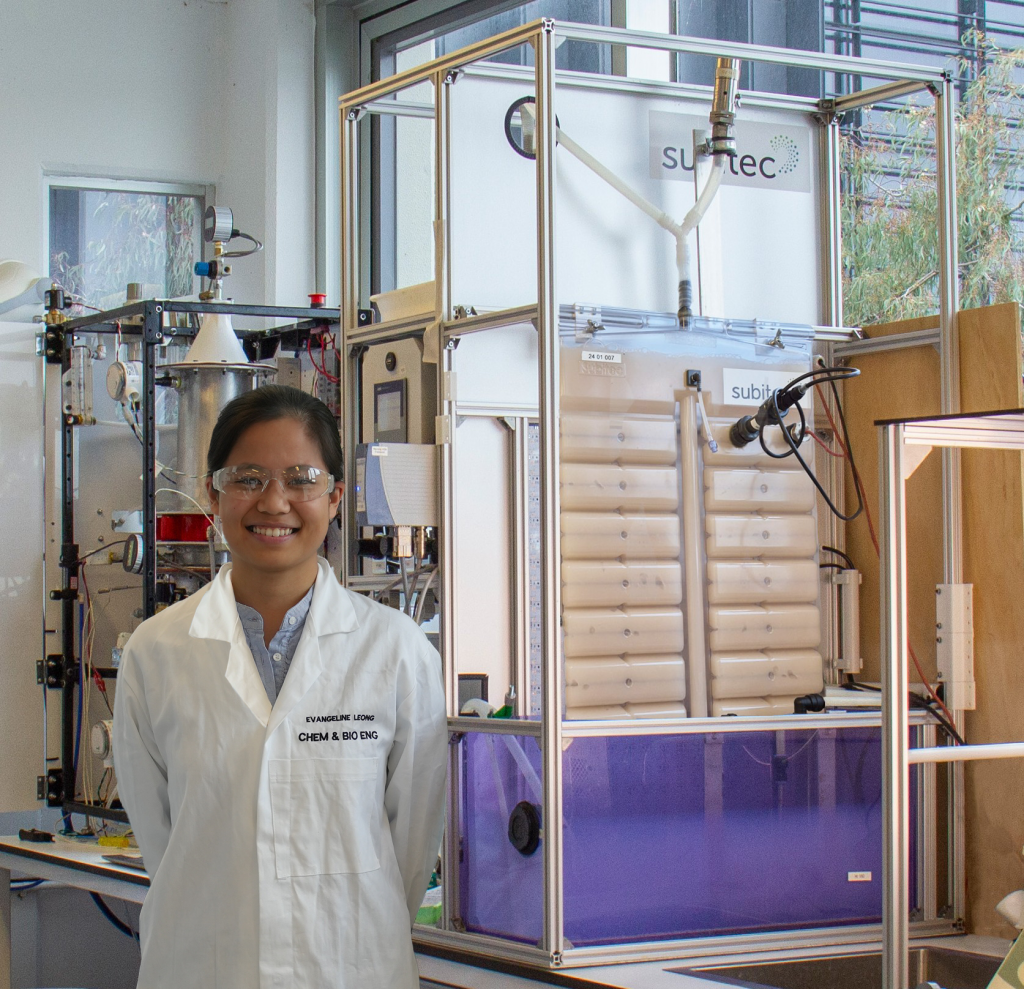

Evangeline Leong

Evangeline Leong

Industry PhD Candidate

Field of research: Chemical engineering

Maksis Darzins

Industry PhD Candidate

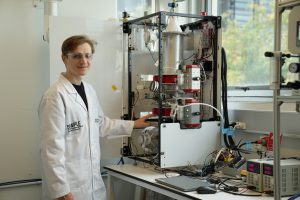

Field of research: Mechanical engineering

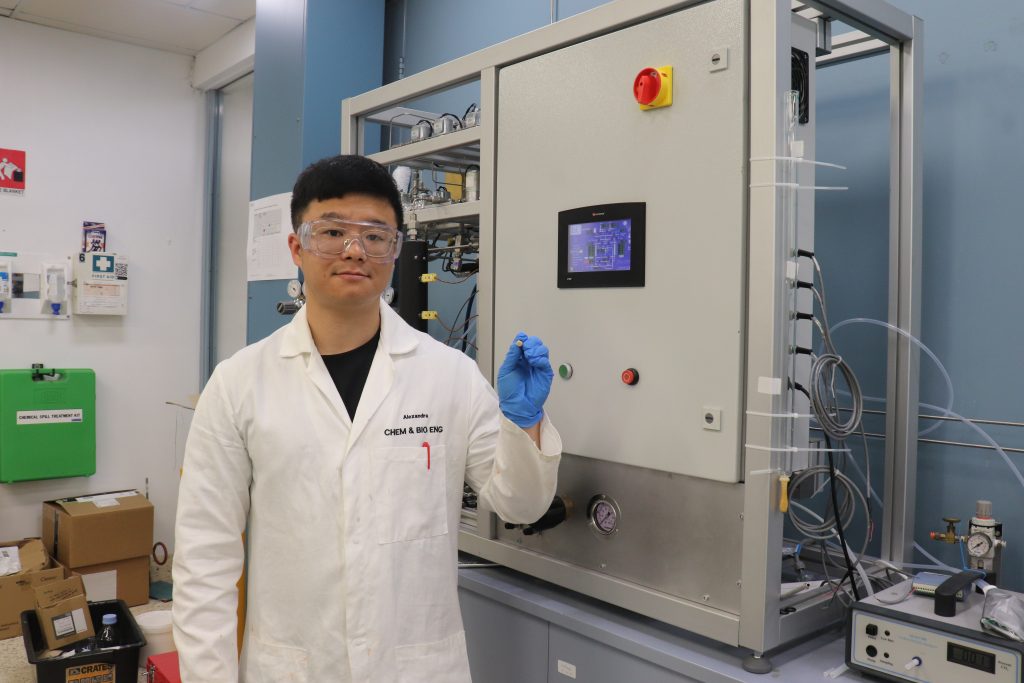

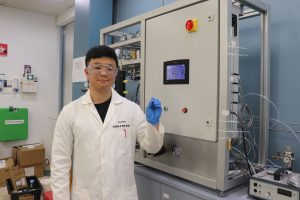

Dr Aaron Guo

Research Fellow

Field of research: Chemical engineering

Monash University, Australia

Research project: Developing a direct air capture system that captures carbon dioxide from the air for carbon reduction and utilisation

Funders: RECARB Hub; Woodside Monash Energy Partnership; Australia Economic Accelerator

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM659

About direct air capture

Given the critical need to find and implement solutions to climate change, direct air capture (DAC) is a rapidly growing field of study and development. “There are a multitude of interesting design challenges that must be solved for the technology to have a tangible impact on climate change,” says Maksis. “Innovative solutions to these problems require creative thinking, which makes the field extremely appealing to work in.” The work is highly rewarding; after all, it is helping solve what many consider the greatest challenge of our time.

DAC is a highly collaborative field, combining skills from many different disciplines. “No individual can solve complex problems like DAC alone,” says Evangeline. “Progress happens when engineers, scientists and innovators learn to communicate across disciplines.” In particular, DAC involves engineers of every type. “Throughout the design process of the pilot system, the team has consulted colleagues in every branch of engineering, including chemical, mechanical, aerospace, electrical, and civil, and each discipline brought their own insights,” says Maksis.

Perhaps the biggest challenge of DAC is working out how to capture CO2 efficiently. “Even though atmospheric CO2 concentrations are much higher than they should be, they are still very low relative to other gases,” says Aaron. “This low concentration makes it difficult to capture CO2 while ignoring other gas molecules, and also means that an enormous volume of air must be processed.”

Pathway from school to direct air capture

At school, get a good grounding in mathematics, physics and chemistry.

At university, Maksis suggests pursuing engineering for the most direct route to DAC research and development. “Chemical engineering and mechanical engineering are the most common, though all engineering fields are relevant,” he says.

Vocational careers can also directly contribute to DAC. “All types of practical professions are needed to support the building and development of DAC plants, as well as management and business professionals to support and help scale the emerging technologies,” says Maksis.

Explore careers in direct air capture

Getting experience in the field is a great way to learn about DAC and whether it could be a good fit for you. Engineers Australia hosts a huge range of resources covering work experience, internships, mentoring and more.

Monash University has a number of outreach programmes for high schools. For instance, Monash Engineering Girls is an engagement programme for high school girls to learn more about engineering careers.

Meet Evangeline

I’ve always been fascinated by how things work and how they are created. As a teenager, I couldn’t decide which area of science I liked best, so I ended up studying all of them at university through a double degree in chemical engineering and biomedical science. Over time, I was drawn to the practicality of engineering, but my biomedical background has also proven incredibly valuable for my current work.

I lead the DAC2BIO programme. My goal is to ensure that the CO2 we capture doesn’t just get pumped underground, but is transformed into useful products. I joined the project because I saw its enormous potential to create technologies that benefit people and the planet. Working with a world-class team of researchers and industry experts is a privilege.

Problem-solving and creativity are essential skills in this line of work. DAC and biomanufacturing are emerging areas, so we often encounter challenges that no one has faced before.

I love being surrounded by brilliant, curious minds. This includes mentors, peers and students. The trust and autonomy that I’ve been granted by my supervisors have allowed me to explore bold ideas and grow as an innovator and leader.

Outside of work, I enjoy quiet time alone or with family. Simple, restful things help me recharge. I’m an introvert who has learnt to be a professional extrovert when needed; so, when my social battery runs out, I return to calm spaces to reset and find balance.

Evangeline’s top tips

1. Develop your interpersonal skills. Get involved in group projects, science fairs or student innovation challenges to practise teamwork and creative problem-solving.

2. Pair your scientific curiosity with empathy and purpose. You will find yourself helping to build a cleaner, more sustainable world.

Meet Maksis

I have always enjoyed building and creating. When I was young, I spent my weekends making custom skateboards that I used to explore the neighbourhood. This passion progressed to a double degree in mechanical engineering and industrial design, which satisfied the creative and academic parts of my brain.

My true passion for mechanical design was uncovered by an extracurricular activity at

university. Monash Motorsport is a student team which engineers, designs and builds race cars to compete in student competitions. This experience honed my engineering abilities and taught me hands-on skills such as welding and machining.

I am the lead mechanical engineer on the DAC project. This involves designing, building, testing and continuously improving the DAC system. This lets me use my skills to create a large positive social and environmental impact.

Our supervisor, Professor Paul Webley, has supported us throughout this project. He is not only passionate about DAC but also dedicated to mentoring and nurturing the next generation of researchers.

Outside of work, I enjoy cycling. Riding in all forms, from the commute to work or long-distance weekend rides, gives me the opportunity to disconnect from the rush of working life and regain balance.

Maksis’ top tips

1. Be open-minded and willing to learn. What we need more than anything is young, bright people to solve current and future challenges.

2. Research is never straightforward. It’s a journey towards innovation, and requires resilience and persistence. Turn your setbacks into motivation.

Meet Aaron

I enjoyed physics more than chemistry when I was young. I’ve since learnt that there are many connections between different fields – and drawing on these connections is vital for solving real-world problems. My bachelor’s degree was in mechanical engineering, my master’s was in thermodynamics, and my PhD was in chemical engineering. All have come together to serve me in my work today.

I am the leader of material development and the lead chemical engineer on the DAC project. Soon after starting the job, my first son was born. It made me reflect deeply on the kind of world we are leaving for the next generation. I started to feel a personal responsibility to help create a more promising future. DAC is one technology that can help make this vision a reality.

The DAC project requires an understanding of materials and process design. But problem-solving skills and persistence are equally important. Research often brings unexpected challenges, so being able to adapt and keep learning is essential.

I love working with an amazing team. Everyone has a can-do attitude and a willingness to solve problems together. Being part of a supportive team makes the work exciting.

Outside of work, I enjoy fitness and hiking. Exercise helps me release pressure, while spending time in nature helps me recharge and come back to work feeling refreshed.

Aaron’s top tips

1. Stay curious and keep learning. Explore new ideas, follow the latest research and don’t be afraid to try new things.

2. Develop problem-solving, creativity and persistence, because research always comes with challenges.

Do you have a question for Evangeline, Maksis or Aaron?

Write it in the comments box below and they will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)

Learn more about research at the RECARB Hub:

futurumcareers.com/tackling-climate-change-with-gas-guzzling-microbes

The post How can we transform carbon dioxide from a greenhouse gas into a valuable resource? appeared first on Futurum.

“}]]