How did a Renaissance printer shape the books we read today?

[[{“value”:”

How did a Renaissance printer shape the books we read today?

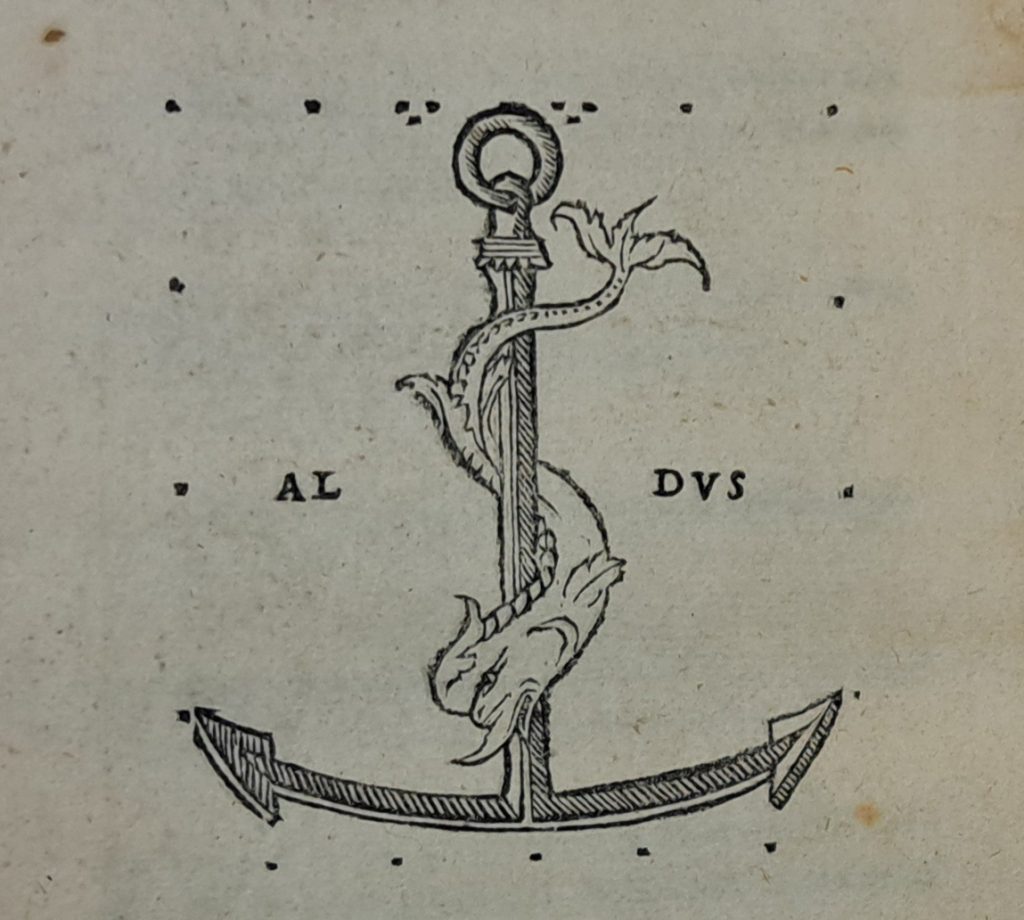

More than five centuries ago, the printer Aldus Manutius permanently changed how people read and shared knowledge with the publication of his ‘portable books’. Now, thanks to the work of Dr John Maxwell and Alessandra Bordini at Simon Fraser University in Canada, his legacy is being preserved and reimagined for the digital age.

Talk like a publishing researcher

Classics — the study of Ancient Greek and Roman/Latin literature and language

Digital collection — a curated selection of digital resources accessible via an online interface

Font — the design of a specific set of letters so they go well together. Originally cut in metal, these are now digital files, e.g., Times New Roman, Comic Sans

Publishing — the artistic and commercial enterprise of producing and promoting written work (in printed or digital form), and making it available to the public

Renaissance — a period of cultural change that began in Italy around 1350 and spread across Europe until the late 1500s, marked by a renewed interest in classical antiquity and advances in the arts and sciences

Typography — the art of arranging characters to create legible and appealing writing, including use of font, letter size and spacing, and line spacing

Books are a familiar part of everyday life. Whether printed or digital, their shape and structure – the use of page numbers, punctuation, chapters and tables of contents – feels natural and universal. Yet the design of the modern book has a history, and many of the features we take for granted were introduced by a pioneering individual – Aldus Manutius, a Renaissance scholar and printer who revolutionised book design and publishing. At Simon Fraser University (SFU), Dr John Maxwell and Alessandra Bordini are making Aldus’s books available online through the Aldus@SFU project, to explore how his innovations influence the way we read today.

Who was Aldus Manutius?

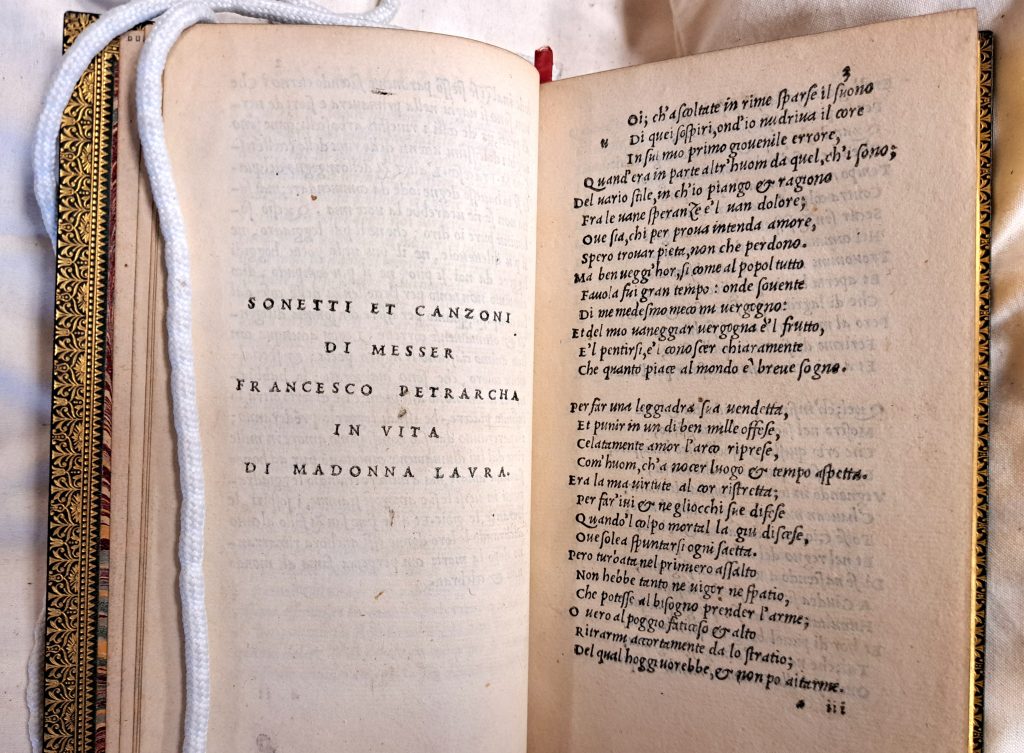

“Aldus Manutius lived from around 1450 to 1515 and is celebrated as Renaissance Italy’s finest publisher,” says Alessandra. Beginning as a classics teacher, Aldus gained international renown as a publisher, helping revive classical learning by printing the major works of the Ancient Greek and Roman worlds. Many of Aldus’s books were the first ever printed editions of these texts, most of which existed in his day only as rare handwritten manuscripts. “Over time, Aldus’s printing company, the Aldine Press, published all sorts of books,” says John. “In addition to classical texts in Greek and Latin, he also published new Italian literature – all the things that a hip, educated person should read!”

“But the Aldine Press was more than a profit-driven publishing business,” continues Alessandra. “Aldus’s workshop was a centre of learning and cultural exchange, and he used the new technology of the printing press to make education and knowledge more widely accessible.” In this way, Aldus continued his role as a teacher while shaping the future of books.

How did Aldus shape the way we read today?

“Only a few decades before Aldus began publishing, there were no printed books at all,” explains John. “Instead, manuscripts were painstakingly copied by hand, so they were rare and extremely expensive.” Even after Johannes Gutenberg invented the printing press in the 1440s, the first printed books closely resembled handwritten manuscripts because that was what people were used to. “They were typically big, impressive and intimidating!” says John. This meant they were heavy and often difficult to handle. “Aldus created books that, for the first time, had a design of their own.”

“Aldus’s successful ‘portable books’ were small-format volumes that could be conveniently held and carried,” explains Alessandra. “While he didn’t invent the concept of pocket-sized books, by combining visual appeal with functionality, he made them more widely accessible.” In this way, Aldus and his portable books popularised the idea of reading not just for study, but for pleasure.

Before Aldus, nothing in book design was standardised. There was no consistency in how books were arranged and navigated, or in the use of punctuation and font. Aldus introduced standardised page numbers and, based on that, contents pages and indexes. Modern punctuation, including commas and semicolons, was developed in the Aldine Press. Aldus also established modern typography, as his books had clear and open text which contrasted with the dense, formal style of medieval manuscripts. His books were printed in italic type, which he modelled on the handwriting of the time, making his books more legible. And many fonts that we still use today (such as Times New Roman and EB Garamond) are inspired by fonts designed at the Aldine Press.

“All these innovations had a lasting impact not only on the design, structure and format of the book, but also on how readers interact with it,” says Alessandra. “Today, it’s easy to take books and punctuation for granted, but every time you write a comma or carry a book with you to read, you are benefitting from Aldus’s contributions.”

How did Aldus@SFU begin?

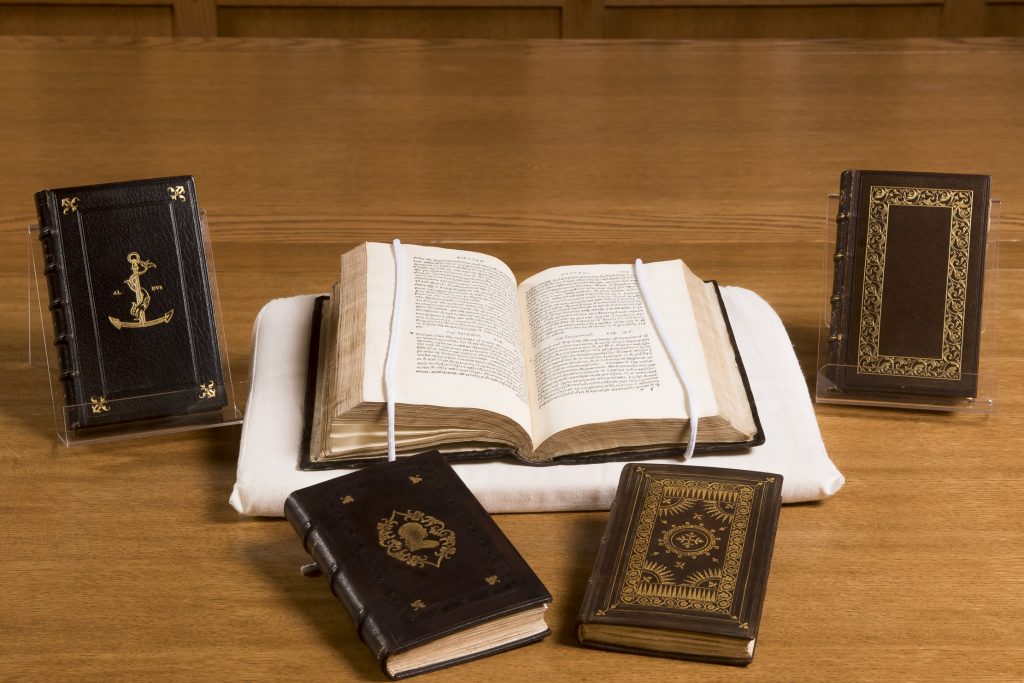

The SFU Library is home to the Wosk—McDonald Aldine Collection, which contains over 120 books published by the Aldine Press between 1495 and 1580. These volumes offer a tangible record of the evolution of modern book design, and in addition to being rare items of historical and cultural importance, they are also admired as beautifully crafted objects.

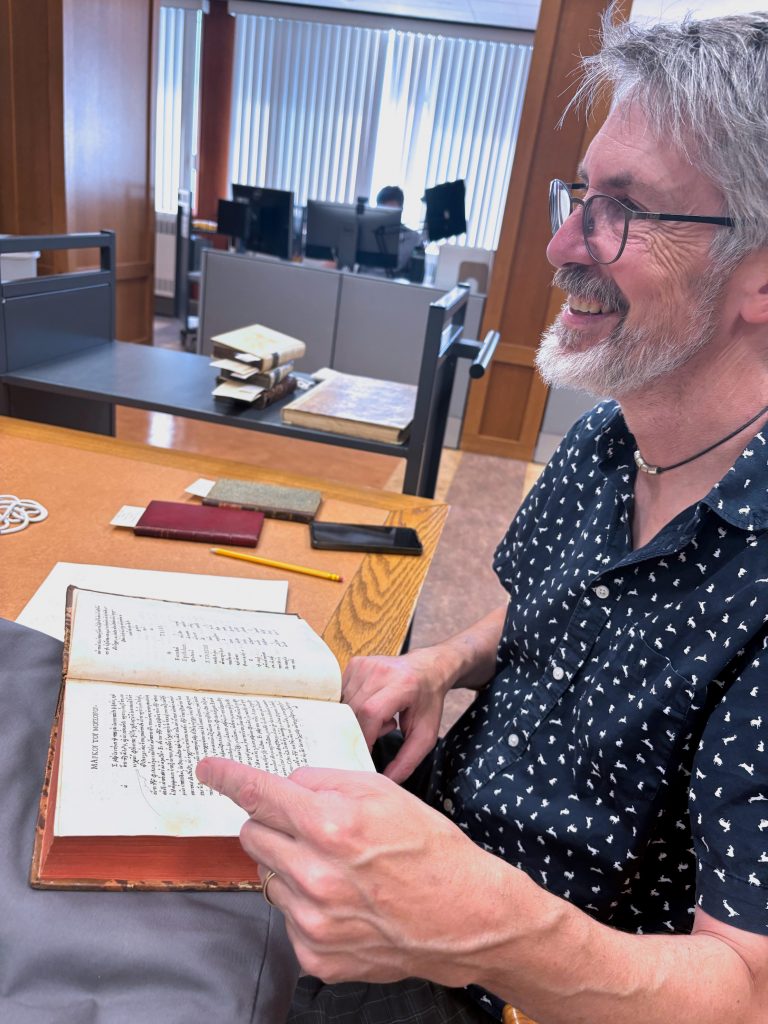

To digitise the collection, each book was scanned by library staff and student research assistants. “The book sits in a cradle with lights and two cameras suspended over it, pointing at the left and right page,” explains John. Page by page, each volume was photographed – a process that took several months to complete. The photos were uploaded to a digital collection, along with metadata for each book, such as the catalogue number, author’s name, publication date, dimension of the pages and notes on typography.

John and Alessandra wanted to make Aldus’s books accessible online so that everyone can appreciate them. “You don’t need to be a book scholar or fluent in Greek and Latin to enjoy Aldus’s works and learn from the stories they embody,” says Alessandra. “We believe – and I have no doubt Aldus would agree – that just because a book is valuable, it doesn’t mean it should be locked away. On the contrary, its value increases when it is shared with others.”

The Aldus@SFU project is more than just the texts themselves; it tells the stories behind the evolution of the book we know today. These volumes show how typography developed, how punctuation and page layouts were standardised, and which works were considered important enough to print 500 years ago. “We take books for granted,” says John. “They’re just there, and nobody thinks about why they are the way they are.” By showcasing Aldus’s books from the early days of publishing, John and Alesandra are opening our eyes to the extraordinary history of this everyday object.

Dr John Maxwell

Dr John Maxwell

Associate Professor

Fields of research: Publishing technology, history of publishing

Alessandra Bordini

Researcher and interdisciplinary PhD student

Fields of research: History of publishing, Renaissance studies

Publishing Program, Simon Fraser University, Canada

Research project: Aldus@SFU: Turning the works of Renaissance printer Aldus Manutius into a rich, public digital resource

Funder: Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC)

Website: alduslibsfu.ca

About publishing

“Publishing is the business of finding an audience for written works of all kinds,” says John. But it is also an artistic enterprise as much as a commercial one. “Publishing is the art of listening to and aligning with the needs of different individual and collective actors – the author, their intellectual work, the public, the market,” says Alessandra. “In book publishing, the creative vision of the publisher is the glue that keeps everything together.” Far beyond merely making money, publishing is about building new communities around books, and ensuring books are meaningful, accessible and culturally impactful.

Reference

https://doi.org/10.33424/FUTURUM633

© National Gallery of Art

© John Maxwell

© John Maxwell

© Shamina Seneratne

What is the future of the book?

While digital media has dramatically changed how we access and share information, it has not replaced the traditional book. “The book market has proved to be surprisingly durable in the face of digital innovation and disruption,” comments John. “In the early 2000s, many people believed that eBooks would make print books obsolete, but that hasn’t happened.”

While eBooks have their uses and supporters, many people prefer the feel of a ‘proper’ book. “When I read for pleasure, nothing gives me more joy than a printed book,” says Alessandra. “However, for research purposes, digital forms have the advantage of being searchable.” On the much-debated question about the future of the book, Alessandra agrees with Italian scholar and novelist Umberto Eco: “The book is like the spoon, scissors, hammer and wheel. Once invented, it cannot be improved.”

Just as Aldus Manutius changed the way books were read in the 15th century, technology is changing our reading habits today. Aldus’s portable books encouraged readers to carry books with them – just as smartphones now let us carry the internet in our pockets. Then and now, the shift was not only about technology, but about how people interact with technology in everyday life.

Pathway from school to publishing

“The most essential thing is a love of books and reading,” says John. The more you read, the better you connect to the culture and world around you – the key sensibility for making good publishing decisions.

In high school, it would be useful to study literature, languages, media studies, art and design.

At college or university, consider an undergraduate degree in literature, journalism, communications, media, business or the arts. However, you can enter the publishing industry with any academic background: “Students with a science background bring valuable perspectives on the world that translate well into thinking about books and publishing,” says John.

Simon Fraser University offers undergraduate and master’s programmes in publishing: sfu.ca/publishing

Explore careers in publishing

Whether you are passionate about literature, design, business or technology, publishing offers the chance to shape public conversation and bring meaningful work into the world.

“Publishers are culture-creators and tastemakers, just like musicians, filmmakers and artists,” says John. “That’s the appeal of working in this industry.”

Publishing offers a wide range of career paths, from editing and design to marketing and sales. Junior roles tend to be in the marketing side of the industry, while those with more experience take on roles such as acquiring and editing new books.

You could also choose an academic career to research different aspects of the publishing industry, like John and Alessandra.

Explore websites of publishing companies and organisations such as the International Publishers Association (internationalpublishers.org), BookNet Canada (booknetcanada.ca), the Association of American Publishers (publishers.org) and the Publishers Association (publishers.org.uk/about-publishing/careers).

Meet John

As a teenager, I wasn’t all that bookish, though I did devour magazines (this was in the 1980s – the golden age for magazines). I was more interested in music and cycling. When I finished high school, I had very little sense of what I wanted to do. I went to university because it was expected, not because I had a goal. I chose to study anthropology, simply because it looked interesting enough to encourage me to go to class each day!

I fell into work as a freelance web designer in the 1990s. Lots of people were getting into web design at that time (it was the early days of the World Wide Web), and in trying to improve my skills I became interested in traditional publishing, specifically design and typography.

One thing led to another, and I returned to university to do a master’s degree in publishing. I then worked in distance education, creating online resources for high school kids in remote locations who couldn’t access a school, which taught me a lot about digital production. I went back to university again for a doctorate in education, then ended up teaching digital media production in the Publishing Program at SFU.

To mark the 500th anniversary of Aldus Manutius’s death in 2015, a colleague suggested we should do something with the Wosk—McDonald Aldine Collection. Alessandra was a master’s student at the time, and we have been immersed in understanding Aldus and his 15th century world ever since.

I’m always surprised by the similarities between the cultural contexts of Aldus Manutius and today. Not only is the book industry strikingly similar (though, of course, we now have online retailers like Amazon), but the tumultuous political landscape of the Renaissance provides food for thought today. Like today, the Renaissance was a time of culture wars, Islamophobia and struggles between tyranny and democracy.

In my free time, I am a devoted amateur musician – I play a few different instruments, sing and tinker with music technology. And I ride my bike. So, the same things I did when I was a teenager!

Meet Alessandra

I was a studious and curious teenager – easy-going on the outside, restless on the inside. Reading and writing gave me an outlet for my maverick nature. I was an avid reader of fiction and, as an Italian native speaker, I bought British and American magazines to improve my English language skills. And my desk drawer was populated with extemporaneous poems, unfinished short stories and letters conveying heartfelt appeals to politicians.

My mother, Paola Pinna, was a talented painter and sculptor. When I was a child, she introduced me to the masterpieces of Renaissance art, and I was absolutely flabbergasted. I developed an interest in the visual arts at an early age which later gave me an appreciation of books as aesthetic objects in their own right.

My career journey has been shaped by my love of language and words – both their musical quality and visual expression on the page. Before coming to SFU, I worked as a literary translator and editor in the Italian book publishing industry. My interest in publishing is grounded in the practical consideration that, as a publisher, you are contributing to bringing a vision to life. I see myself as both a thinker and a maker, and publishing is that rare space where the exploration of ideas and the refinement of craft blend harmoniously.

I enjoy studying the works of Aldus Manutius because I get to engage with incredible, finely printed books that carry 500 years of history. These aren’t just magnificent objects to look at, but also invaluable records of our vibrant intellectual and cultural tradition. These books, and the cultural richness they represent, are a constant source of wonder and inspiration for me.

Meaningful and long-lasting friendships are formed around books. One rewarding aspect of the Aldine digital initiative is connecting with colleagues, students and librarians who share my interests and values.

Other than reading, I enjoy urban photography, long walks in nature with my partner Jeff, and doing Pilates. I love hanging out with my cat Lila, who also loves to devour paper books – only in a literal way!

Do you have a question for John or Alessandra?

Write it in the comments box below and they will get back to you. (Remember, researchers are very busy people, so you may have to wait a few days.)

The post How did a Renaissance printer shape the books we read today? appeared first on Futurum.

“}]]